Part 2: The JSA, The Space between Political Charades and Tragedy

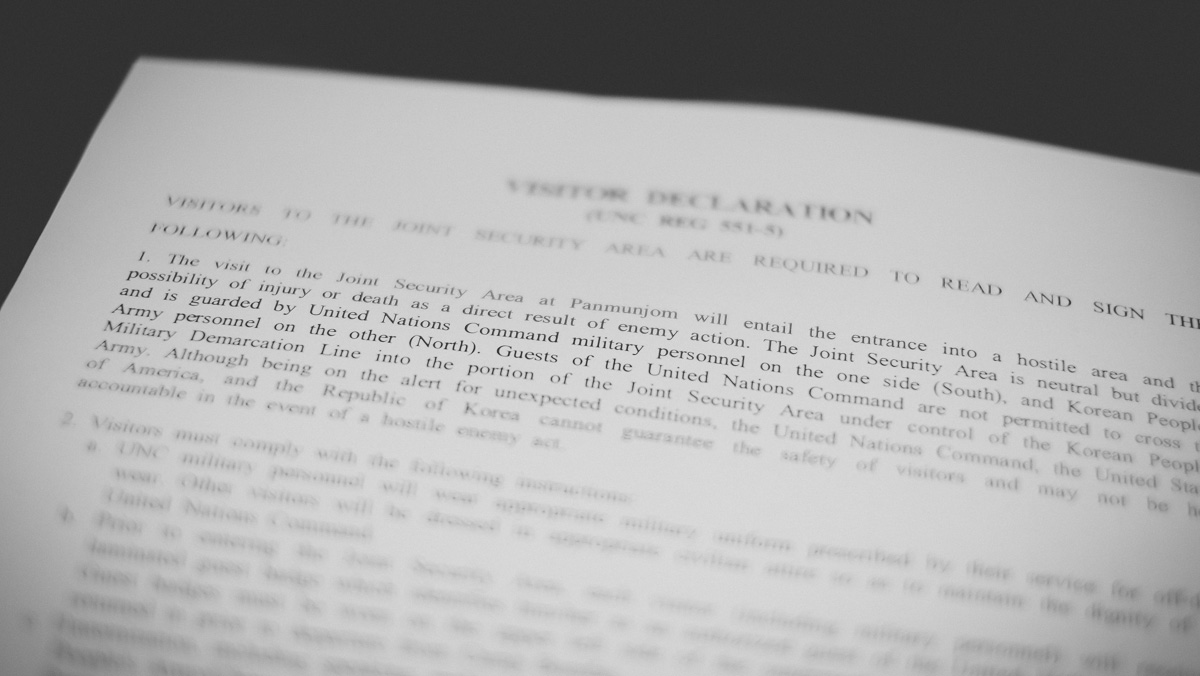

The weather forecast was not good that day. Rain with thunderstorms. But, the rain seemed to be holding off and the weather, albeit oppressively hot and humid, was at least making for decent pictures. As we wrapped up our last stop before the Joint Security Area (JSA), the skies turned dark and growled with thunder. As we traveled toward Camp Kim, the rain just couldn’t hold off any longer. Large, heavy raindrops started pouring down as our US/EU military escorts boarded our Koridoor tour bus to check our passports and take over from our USO tour guide. We scurried inside the visitor center where we were given our second waiver of liability for the day. It read: The visit to the Joint Security Area at Panmunjom will entail the entrance into a hostile area and the possibility of injury or death as a direct result of enemy action. … Although being on the alert for unexpected conditions, the United Nations Command, the United States of America and the Republic of Korea cannot guarantee the safety of visitors and may not be held accountable in the event of a hostile enemy act.

The visit to the Joint Security Area at Panmunjom will entail the entrance into a hostile area and the possibility of injury or death as a direct result of enemy action.

Although expected and precautionary, signing this waiver did make you appreciate the volatility of the area we were about to enter. After signing our lives away, Private First Class Denochick (one of our US Military escorts) recited, from memory, a history of the war and of the DMZ. He explained, barely stopping to breathe (I empathized with those whose first language was not English, as I even had to work hard to keep up with his presentation), that the peninsula had been divided near the 38th parallel into Soviet and Allied-overseen territories after WWII. This line was never meant to create two countries, but rather two areas of responsibility. Nonetheless, the North launched an attack on the South in 1950, cornering southern forces to the tip of the peninsula, which the South, along with the Allied forces, pushed back to the Chinese border, nearly taking the whole peninsula. Then entered the Chinese, and joined with the North, they pushed the Allied forces south until the two sides were back to square one: the 38th parallel. The DMZ was eventually created by extending 2km north and south from the last point of combat.

The waiver where we signed away our lives, more or less, for access to potentially hostile territory.

After we finished our briefing, we handed in our waivers and filed onto new busses, this time operated by US/UN military. Luckily, the rain was abating and our hope was renewed that we would be able to fully experience the JSA. Our military escorts pointed out several things along the way, including the active minefield, the turn-off to the South Korean village of Daeseong-dong, observation towers and anti-tank blockades that could be employed in the event of an invasion. We were further briefed as to how we must behave once we arrived at the JSA: no pointing, gesturing or signing at anyone on the North Korean side. No abrupt movements. No photographing anything south of the line (we were only allowed to photograph North Korea). Give adequate distance to the ROK soldiers. Move through quickly and stay shoulder to shoulder with the person next to us. After a day of bizarrely touristy stops with gift shops, both the tension and excitement swelled around us.

After a 10 minute ride through the 2 southern kilometers of the DMZ, our bus parked at a large building, which we came to learn was the Freedom House, built on the South Korean side as a meeting place for family reunions. Sadly, it had yet to be utilized as such as the North had prevented each planned use. It’s here that you start to realize the implications on the daily lives of those whose families straddle the Military Demarcation Line (MDL). It is also here where you start to understand the drastic cultural and lifestyle changes that happen once one crosses this line, now less than a hundred meters before us. As we exited the Freedom House, we passed by ROK soldiers who were presumably watching us, yet you would never know through their dark military RayBans that shielded a better portion of their faces. Their statuesque figures all assumed the same taekwondo stance: arms ever slightly bent at their sides with fists tightly clenched and every muscle tensed and ready to strike; feet shoulder-width apart; shoulders back and chests protruding forward; gaze presumably fixed directly forward. London’s beefeaters have nothing on these guys, as you have the impression that even the slightest flinch could turn their bodies into lethal weapons. The sentries at the JSA are all hand-picked: they all have 4 or 5 blackbelts in a form of martial arts, and are among the largest and tallest of the ROK soldiers, giving them both the air and capacity to be intimidating fighters.

Our two single-file lines exited the Freedom House and were finally sharing this open-air space with the enemy. I peered across into North Korea where we saw another group of visitors, presumedly tourists, taking in the JSA from the other side of the line. I couldn’t help but wonder what their lives are like. How they were experiencing this facility. What they were being told about what lies on the other side. How they were viewing ME. I gazed around me and took in the bizarrely docile scene. I was apparently now looking at the most dangerous line in the world and at the most untrusted country in the world. Yet the scene was extraordinarily banal and calm.

Our first view of the JSA. We were not the only visitors as there was a group also visiting from the North.

Before me lay the infamous concrete curb that separated two distinct types of pavement. One belonging to South Korea. The other belonging to North Korea. There it was. The line. The most dangerous line. Soldiers guarded both sides, but in a very different manner. Those of South Korea faced North Korea, although half-shielded by the buildings in case of attack. We were told that their posture was to communicate to potential defectors that they will be welcomed and protected. North Korean soldiers also faced North Korea, which was described as a demonstration of force against defectors… that they would be caught and prevented from going further south. Interestingly though, the Northern soldiers are frequently absent from their posts. We were later told we should take photos of the North Korean sentries as they rarely come out… as though we were at a zoo and the exotic animal emerged for a chance-viewing.

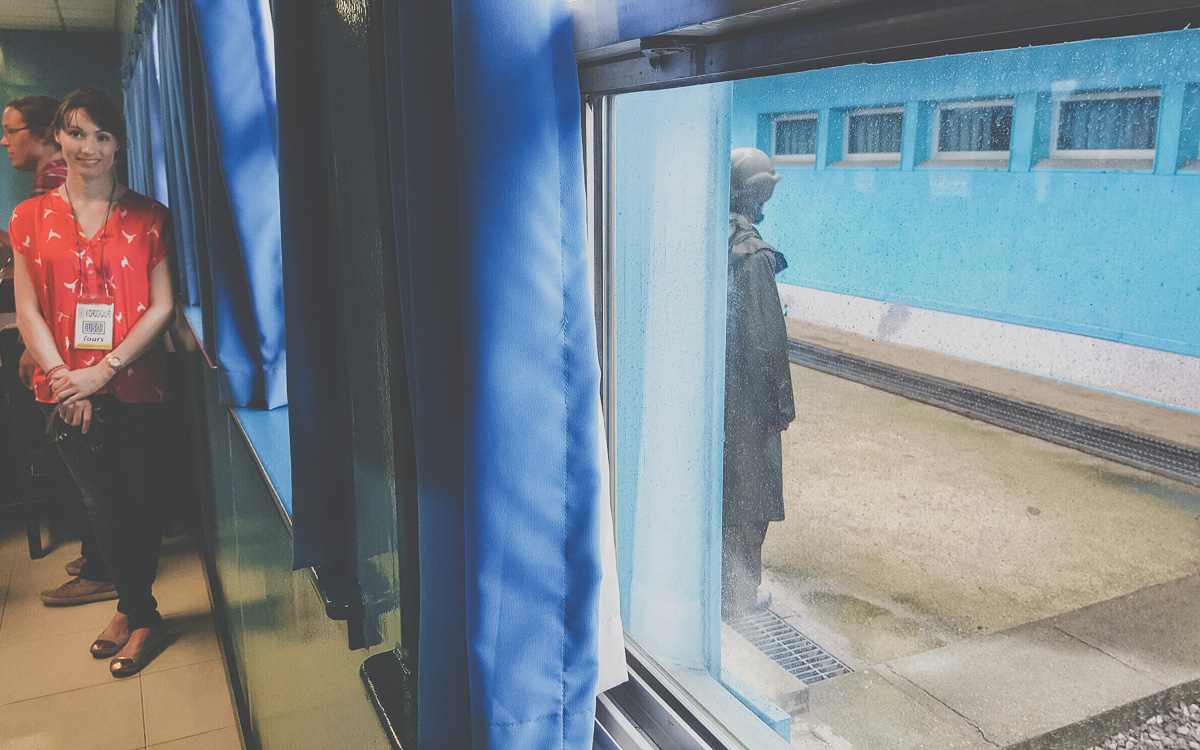

We were quickly ushered into the blue house, where meetings take place between the two Koreas. Apparently, the conference room isn’t actually used that frequently for bi-Korean summits, but more frequently by aid groups and allied forces. We were told that it had been years since the North and South had come together in that room, yet they did actually meet there a few days after our tour in response to the landmine attack that took place the previous week and following escalating tensions. Immediately upon entering, I saw a conference table supporting a lone UN flag, and microphones protruding from the wooden surface. Another statuesque ROK solider straddled the line, never flinching as we entered the room. As Jérôme and I were among the first to enter, we were told to move around to the other side of the table so there would be sufficient space for our whole group to enter. I knew exactly what that meant: we were officially standing in enemy territory. I motioned to Jérôme to look out the window and note that we had in fact crossed the line, quickly snapped a photo of our feet, and tried to take in this surreal moment to which my traveling counterparts seemed oblivious. I gazed across the table with a twinge of satisfaction as I waited for Denochick to address our group.

As the group finished assembling, he discussed the uses of the room, including the table around which we were gathered. He pointed out the microphones that recorded everything that was said in the room, and their cable which ran along the MDL. He then confirmed “so half of you are now standing in North Korea, while the other half are relatively safe in South Korea,” striking an electric buzz of satisfaction and envy amongst our comrades. My twinge of satisfaction returned as I noted my southernly-positioned counterparts looking longingly in our direction, as though our experience was both more rich and dangerous than theirs.

Suddenly, while our soldier continued to talk, there was motion on the other side of the dirty windows. A North Korean soldier peered in at us and then quickly vanished. There were 2-3 Northern soldiers now guarding “the curb” on either side of the conference room, and you had to wonder if this was all a display of theatrics and entertainment. The surveying soldier encircled the northern side of the building and observed us through each window, serving to be quite the distraction from our tour presentation in progress. We locked eyes several times as I attempted to get a photo of him looking in. He was proficient at avoiding the camera, and thus it became a bizarre game of cat and mouse in which we engaged for several minutes. As the presentation concluded, of which I recall very little, we were instructed to take obligatory selfies with the ROK soldiers in the room with us as well as the northern DPRK zoo-like attraction happening on the other side of the walls, because we were apparently some of the lucky few that actually got a sighting.

Do you ever have the feeling that you are being watched? I played cat-and-mouse for a while with this soldier before I was able to capture a few fleeting glances.

Our presence was certainly not being ignored. The ROK soldiers remained stoically poised, but those of the north shifted their glance and inspected our group through the windows at every opportunity. They seemed slightly unnerved by our presence.

Soldiers moving around on the northern side of the conference buildings, only visible through the windows. Again, there wasn’t a moment where were weren’t being inspected.

ROK soldier guarding the northern door in the conference room. How exactly do you pose for a photo with a Korean soldier? Smiling seems weird, but being too stoic seems like a mockery. In other news, I’m pretty confident I was NOT giving him the 12″ of space that we were instructed to leave.

Sure enough, in the moments between exiting the building, crossing the small road, and retaking our positions on the steps of the Freedom House, the DPRK soldiers had seemingly evaporated. I have no idea where the went, but they did not reemerge for the group that followed us into the conference room. Private Denochick continued to explain the various buildings at the complex, including the points from which Northern soldiers were positioned and watching us, affectionately calling one of them “Bob.” At one point, I squatted down to get a better angle for a photograph, for which I was scolded. Another tourist stepped off the platform and onto the top step of the Freedom House, for which she was scolded. Another took a photo apparently aimed at something in the South, for which she was scolded. So many rules. Denochick then told us that we had made more mistakes and gotten in more trouble than another other group he had escorted. I’m thinking someone didn’t do a good job of explaining the rules, as our group was hardly rebellious.

Everywhere we looked, we were being surveyed by the northern DPRK soldiers. The white post protruding from the bottom right of the photo is the Military Demarcation Line. These white posts are the only visible physical boundary and appear every few meters.

We were instructed to re-form our buddy lines and paraded back into the Freedom House, past several ROK soldiers and off to other areas in the southern DMZ. A photo-ban was put in place until further notice. Our next stop was a check-point that was surrounded on three sides by the north, making our photo restrictions much easier to follow. Here we could see the little white posts that dotted the MDL; not much in the way of a border. We had a great vantage point of the propaganda village and it’s massive flagpole, and our crew of military personnel spent some time giving us interesting facts about the DMZ. We snapped photos and selfies of the truly beautiful landscape, retaking the same photos over and over as each moment we were captivated again by its beauty. Emerald forests backed by cobalt mountains, melting into the golden glow of the setting sun. Korea turned out to be one of the most beautiful countries I’ve ever visited, and the North is certainly not an exception. It looked so majestic and serene—how could this land be the cause of so much unrest and trouble?

Our military guides pointed out interesting sights along the panorama, including another white marker post in the right side of the photo.

A frequency jammer seen over the left shoulder of Private Foster serves to isolate the Northern Korean people from outside influence.

Our last sighting within the JSA was The Bridge of No Return, where our bus momentarily stopped so we could look and take photos out the window. It was used for prisoner exchanges at the end of the Korean War in 1953. The name originates from the claim that many war prisoners captured by the United States did not wish to return home. The prisoners were brought to the bridge and given the choice to remain in the country of their captivity or cross over to the other country. However, if they chose to cross the bridge, they would never be allowed to return (Wikipedia). If I am doing my math correctly, over 135,000 soldiers have been exchanged over this bridge.

The photo-ban was back in effect and we traveled back through the remaining southern portion of the DMZ. Upon our arrival, we were told we had 10-15 minutes to visit the exhibition center, shop for souvenirs and buy ice cream. I had heard good things about the North Korean blueberry liqueur you could only buy at the DMZ, but after discovering it came with the hefty price tag of 120,000 won (~$100 at the time), I opted to buy a single note of North Korean currency. Somehow, this felt like a less offensive or insensitive souvenir than the scads of t-shirts, military gear, trinkets and pieces of barbed wire you could buy. The presence of the souvenir shops at each point of interest was mildly irritating to me, but I guess where there is a demand, there will be an offering.

After our time in the exhibition center and gift shop, we reboarded our Koridoor bus and headed back to Seoul, retracing our path out of the DMZ and onto the lonely roads. The trip back served as a time of reflection and decompression.

…

Read Part 1 The Journey to the DMZ’s Joint Security Area

Read Part 3 Our Last Glimpses of North Korea and Further Reflections from the DMZ

No Comments